‘A policeman never looks away.’

‘A policeman never looks away.’

When it was originally published in German in 1958, The Pledge bore the provocative subtitle Requiem for the Detective Novel. This was dropped when the novel was translated into English – there’s no sign of it my edition – but it doesn’t take long to see how apt it is. For The Pledge is a remarkable book: precise, challenging and – in places – callous. Whilst the novel’s focus is a murder, a detective, and an investigation, it lacks the final resolution common to the genre. This makes it feel very contemporary, a book with an uncompromising message: that justice is a myth, chance makes fools of us all, and evil crimes often go unpunished.

Framing the main narrative in The Pledge is the story of a crime writer visiting a small Swiss town, where he delivers a lecture on ‘the art of writing detective stories‘. Returning to his hotel, the unnamed writer befriends a retired policeman, Herr M., formerly the head of the Zurich police. M. offers the writer a lift back to the capital the following morning, which he accepts; and it is during this journey that M. tells the story of one of his former officers, Inspector Matthäi, whose narrative forms the bulk of The Pledge.

Just days before his retirement, Matthäi is called to a small town where the body of a young girl has been found in the woods. Matthäi travels out with several other officers to oversee the investigation – and it is here that his unbending sense of responsibility first reveals itself, a characteristic that will lead to his eventual undoing. Of all of the policemen, Matthäi is the only one in the group able to look at the body. In his own words, ‘A policeman never looks away.’

This belief – tied to the others’ reluctance to step forward – also ensures that Matthäi is the one who tells the dead girl’s parents of her murder. It is whilst doing so that Matthäi makes the pledge of the title, in one of the book’s most quietly unnerving moments:

‘Who is the murderer?’ she asked in a voice so calm and matter of fact that Matthäi was chilled.

‘I intend to find that out, Frau Moser,’ the inspector said, impelled solely by the desire to leave this place immediately.

‘By your soul’s salvation?’

The inspector was taken aback. ‘By my soul’s salvation,’ he said at last. What else could he do?

Given Matthäi’s imminent retirement, the case is handed over to a colleague, who believes the travelling pedler who found the body is guilty. After a long interrogation, he confesses to the crime – ‘that was not legal, of course,‘ recollects Herr M.; ‘but in the police force, after all, we cannot observe regulations to the letter.’ The pedler later commits suicide in his cell, leaving the truth of his guilt unresolved. Matthäi is shaken by this turn of events; his guilt at not preventing it, combined with his promise to the murdered girl’s parents, drive him to investigate further, and he soon links the crime to the earlier murders of two young girls.

This is the point at which Matthäi begins to unravel, and his single-mindedness – such an asset when he was a detective – starts to work against him. Now convinced that a killer is still at large, and desperate to catch him, Matthäi formulates an audacious plan: he will use another young girl as bait, in order to flush the killer out. The enormous risks involved in this plan show just how far Matthäi has been pushed; his only concern is honouring the pledge he has made and apprehending the murderer. With immense meticulousness, Matthäi builds his trap with clockwork precision and waits for his prey.

But even this is not enough. As Herr M. chides the crime writer towards the beginning of the book, ‘reality can be only partially attacked by logic.‘ The problem with much detective fiction, as M. sees it, is that ‘in your novels chance plays no part… You don’t try to get mixed up with the kind of reality that is always slipping through our fingers. Instead, you set up a world that you can manage. That world may be perfect – who knows? – but it’s also a lie.’ In spite of his careful planning, Matthäi is also destined to become a victim of this lie – and the failure of his plan comes at an enormous cost, both to himself and those around him. It is not until the novel’s final scenes that we learn the true nature of his defeat, during a climax which is simultaneously nauseating and banal.

Operating at these extremes, Matthäi forms an interesting contrast to his former chief, Herr M., who is much more matter-of-fact. Police work is about facts, the balance of probabilities, and what can be proven. Discussing the guilt of the pedler, Gunten, Herr M. remarks ‘he has something nasty about him, it’s true… But that is a subjective reaction, gentlemen, not criminological evidence. We aren’t here to work on intuition.‘ Which sounds to me very much like a criticism of his fictional counterparts.

Unlike Matthäi, M. also accepts that the powers of the police should and must have limits. If Matthäi is correct about the killer, in order to catch him the best the police can hope for is that he makes a mistake when he kills again. ‘That sounded cynical, I admitted, but it was not: it was only terrible to think of.‘ Contrast this with Matthäi, who is willing to go to any lengths; to give up everything – including his sanity – to see his investigation through to the bitter end.

The passages quoted above give some indication of just how neatly and devastatingly written The Pledge is. Dürrenmatt’s prose is clean and precise, and very striking – early on, the hungover crime writer looks out of the car window onto the dull landscape beyond: ‘Winter seemed unwilling to abandon this part of the country. The city was encircled by mountains, but there was nothing majestic about them. They rather resembled huge dumps of earth, as though an immense grave had been dug here.’ The Pledge is one of those books that at first glance seems simple; but its shallowness is deceptive, and there is a depth that only emerges through repeated readings. It is a book that I know I will return to.

The passages quoted above give some indication of just how neatly and devastatingly written The Pledge is. Dürrenmatt’s prose is clean and precise, and very striking – early on, the hungover crime writer looks out of the car window onto the dull landscape beyond: ‘Winter seemed unwilling to abandon this part of the country. The city was encircled by mountains, but there was nothing majestic about them. They rather resembled huge dumps of earth, as though an immense grave had been dug here.’ The Pledge is one of those books that at first glance seems simple; but its shallowness is deceptive, and there is a depth that only emerges through repeated readings. It is a book that I know I will return to.

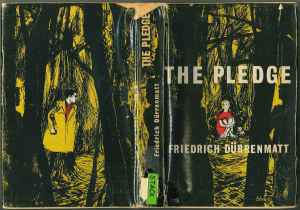

Once I’ve bought my own copy, of course. I acquired this one from my local library, and one of the more unexpected joys of reading it was the reminder of the intense pleasure to be had from the book as a physical object. The copy I borrowed is the first English translation, published by Jonathan Cape in 1959. As well as being neatly-sized, and printed on pleasingly heavy paper, it features a beautiful dust jacket designed by Peter Edwards. His illustration is one I could look at for hours, not only because of the skill displayed in it, but also the way it casts new light on the narrative – a remarkable thing for any artist to be able to do.

The Pledge is an extraordinary book, and one that deserves to be more widely read. Eminently quotable, it is a landmark in 20th century European crime fiction. I look forward to reading Dürrenmatt’s two earlier detective novels, Suspicion and the intriguingly titled The Judge and His Hangman. The Pledge certainly seems to foreshadow much modern work in the genre, with its conflicted ‘hero’, realistic portrayal of the police, and the ways in which blind fate bring the storyline to a close. These tropes are now much more commonplace; the fact that the author was using them almost 60 years ago is nothing short of astonishing.

I’m officially intrigued by this book.I can’t believe no one has made it into a movie!

It’s well worth a look. And there has been a film version, also worth seeing and very faithful to the original – directed by Sean Penn, and starring Jack Nicholson. Try and catch it if you can

I read and enjoyed The Pledge a year ago (I think). If only he could have seen the truth. I bought The Judge and His Hangman earlier today. I agree with you in that this author should be more widely read. I’ve never seen the film version.

Worth seeing – very faithful to the book, even down to the hedgehogs…

Thanks for the link, much appreciated!